[Norsk]

Author Walter Keim, M.Sc. Email: walter.keim@gmail.com

Medical Research Archives, [online] 11(12). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v11i12.4866 [maintenance added]

Active schizophrenia is characterized by psychotic symptoms that can include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, trouble with thinking, and a lack of motivation. The introduction of antipsychotics in the 50ties was called a revolution for the treatment of schizophrenia and psychosis and is now a cornerstone of treatment. The effects are considered well documented. Guidelines suggest that all patients be offered antipsychotics. Nearly all patients are medicated. Concerns have been raised about non-responders, and there is no evidence for long-term effects. The validity of the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Mental Disorders (DSM) is controversial and discussed. Patients experience side effects and low benefits and try to stop. This is considered non-conformance, which can lead to relapse. Therefore, caregivers consider medication necessary and use forced drugging. Antipsychotics reduce psychotic symptoms. New patient laws in many countries aim to promote recovery.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health has called 2019 for «World needs a "revolution" in mental health care». "There is now unequivocal evidence of the failures of a system that relies too heavily on the biomedical model of mental health services, including the front-line and excessive use of psychotropic medicines, and yet these models persist". However, this proposal is highly controversial for clinicians.

World Health Organization (WHO) followed up 2021: “New WHO guidance seeks to put an end to human rights violations in mental health care”. "This comprehensive new guidance provides a strong argument for a much faster transition from mental health services that use coercion and focus almost exclusively on the use of medication to manage symptoms of mental health conditions to a more holistic approach that takes into account the specific circumstances and wishes of the individual and offers a variety of approaches for treatment and support".

This is highly controversial; however, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) supported the WHO proposal with a guideline to reform legislation in order to end human rights abuses and increase access to quality mental health care. A realistic path to implement WHO treatment improvements seems to need the courage of legislators to follow OHCHR suggestions and a shift of paradigm.

The scope is to evaluate studies during 60 years use of antipsychotics and find out if a shift of paradigm of treatment is supported. Treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics started in the 50ties. After the introduction of antipsychotics, also called neuroleptics, comparisons of outcomes were conducted. Odegard1 compared the pattern of discharge from Norwegian psychiatric hospitals before and after the introduction of psychotropic drugs. The study of hospital admission and discharge records in 1948/52 and in 1955/1959 determined that while there may have been a slight improvement in discharge rates after chlorpromazine arrived in asylum medicine, the total number of readmissions “increased 41.6%,” which the researchers described as “characteristic of the drug period.” This study did not assess functional outcomes for the discharged patients.

Bockoven et al. conducted in 1975 a "Comparison of two five-year follow-up studies"2: 1947–1952 and 1967–1972. They found: «One unexpected finding is the suggestion that these drugs might not be indispensable; in fact, they might actually prolong the social dependency of some discharged patients.» Relapse rates increased from 55% in 1947 cohort to 69% in 1967.

In 1961, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) conducted the first well-controlled study of antipsychotics using the Global Rating of Improvement scale3. After six weeks, the drug-treated patients had a greater reduction in their psychotic symptoms and were doing better than with a placebo. This was evidence of short-term efficacy. However, many of the placebo-treated patients also improved. The diagram in Fig. 2 of the report makes it difficult to estimate values. Minimal, much, and very much improved seem to add up to approx. 93%, with 58% improvement in the placebo group, i.e., a 35% difference. The Number Needed to Treat (NNT) is 3. Three patients have to be treated in order to help one improve psychotic symptoms. Fig. 7 shows that mildly, moderately, and borderline ratings cover more than 55% of post-treatment improvement.

The drug-treated patients fared better than the placebo patients over the short term of six weeks. However, when the NIMH investigators followed up on the patients one year later, they found, much to their surprise, that it was the drug-treated patients who were more likely to have relapsed. Drugs that were effective in curbing psychosis over the short term were making patients more likely to become psychotic over the long term (Schooler et al. 1967)4 . 80 percent of placebo patients were regular in their work attendance, but 56% received some drug therapy.

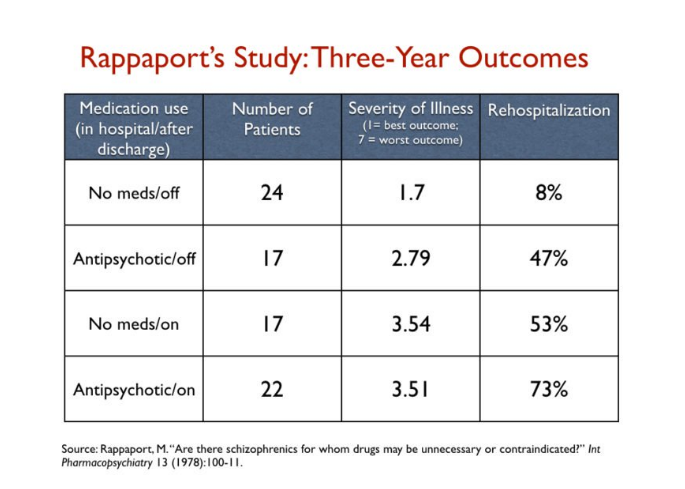

Maurice Rappaport5 randomized 1978 80 young males newly diagnosed with schizophrenia at Agnews State Hospital: ”This study reports that there are schizophrenics who do relatively well long-term without the routine or continuous use of antipsychotic medication. Specially selected young males undergoing an acute schizophrenic episode were followed, after hospitalization,for up to three years.” As such, he ended up with four groups at the end of three years6:

“a) those treated without antipsychotics in the hospital who stayed off the drugs during the follow-up.

b) those treated without antipsychotics in the hospital who then used drugs in the follow-up.

c) those treated with antipsychotics in the hospital who got off the drugs in the follow-up.

d) those treated with antipsychotics in the hospital who stayed on the drugs during the follow-up.”

Figure 1: Rappaport Study: Three-Year Outcome7

“Many unmedicated-while-in-hospital patients showed greater long-term improvement, less pathology at follow-up, fewer rehospitalizations and better overall function in the community than patients who were given chlorpromazine while in the hospital.”

The patients that arguably fared the worst were the last group—those on antipsychotics throughout the study. Seventy-three percent of this group had been rehospitalized.

Leucht et al. 20098 studied “How effective are second-generation antipsychotics”. There was no significant difference between first- and second-generation antipsychotics. However, the effectiveness of the results over time decreased considerably due to a better study design. Acute symptom reduction was found in 41%, while placebo was found in 24%. The absolute responder rate was 18%, resulting in NNT 6. Studies with acute, minimal, and good responses were included. In two-thirds of the studies, participating patients obtained minimal symptom reduction and one-third good symptom reduction.

Leucht et al. 20129 studied maintenance treatment and concluded that “(N)othing is known about the very long effects of antipsychotics compared to placebo”. Future studies should focus on the long-term outcomes of social inclusion and the long term morbidity.

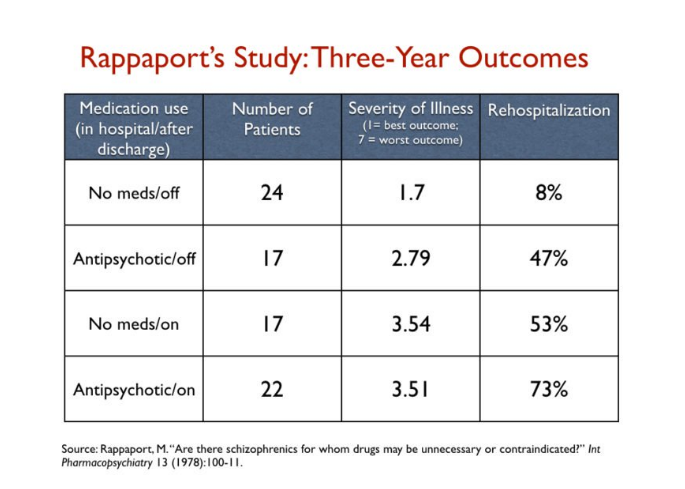

Leucht et al. 2017 (“Sixty Years of Placebo-Controlled Antipsychotic Drug Trials in Acute Schizophrenia”)10 examined both minimal and good symptom reduction. "Good response" for symptom reduction for acute psychosis was 23% minus 14% placebo, i.e., 9% due to the drug. 91% do not benefit from antipsychotics. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to evaluate symptoms.

Figure 2: Good acute symptom reduction

For minimal symptom reduction, 51% minus 20% placebo, i.e., 21% due to antipsychotics, results in NNT 5, which corresponds to NNT 6 from Leucht et al. 2009 with two thirds based on minimal symptom reduction.

Science journalist Robert Whitaker has 200411 updated 201612 concluded in “The case against antipsychotic drugs: a 50-year record of doing more harm than good” studied the evidence: “Although the standard of care in developed countries is to maintain schizophrenia patients on neuroleptics, this practice is not supported by the 50-year research record for the drugs.” Additional evidence from many studies has documented long-term harm. Aprox. 60% of hospital patients did well after discharge and avoided rehospitalization before antipsychotics were introduced.

Sohler et al. 2015 13 found in “Weighing the Evidence for Harm from Long-term Treatment with Antipsychotic Medications, A Systematic Review” no evidence for long term treatment: “We believe the pervasive acceptance of this treatment modality has hindered rigorous scientific inquiry that is necessary to ensure evidence-based psychiatric care is being offered.” But studies showing harm are either excluded or criticized as “inadequate to test the hypothesis.” The authors “note(d) that our data also failed to determine whether long-term antipsychotic medication treatment results in greater benefit than harm on average when assigned or prescribed”. Therefore,, evidence supporting recommendations for long-term, continuous treatment with antipsychotic medication for all people with schizophrenia is lacking.

Robert Whitaker answered 201614. “Sohler focused on a particular slice of that evidence base, which had the effect of excluding the first NIMH study; Carpenter’s psychotherapy study; the WHO cross-cultural studies; the dopamine-supersensitivity worries; Chouinard’s reports of drug-induced tardive psychosis; and the MRI studies. It is that larger body of evidence that needs to be considered...If there is a lack of evidence that antipsychotics provide a long-term benefit, then—given that the drugs have so many adverse effects—there is reason to rethink treatment protocols that urge long-term use... a close look at the 18 studies reviewed by Sohler reveals that their results, in fact, fit within the larger narrative of science reported in this Mad in America Foundation paper. ” Many studies have been excluded. e.g. natural studies because randomization was missing.

However, nearly all randomized controlled trials (RCT) use a “wash-out” period before randomizing to placebo or drug because it was considered unethical not to give antipsychotics. Both Carpender and Bola 2011 found that studies with antipsychotics-naive participants are safe and therefore not unethical.

Dalsbø et al. (Norwegian Institute of Public Health)15 concluded 2019: “ It is uncertain if antipsychotics compared to placebo affects symptoms in persons with early psychosis” because antipsychotic-naive participants are missing.

Iversen et al.16 found 2018 in “Side effect burden of antipsychotic drugs in real life - Impact of gender and polypharmacy”: Use of antipsychotics showed significant associations to neurologic and sexual symptoms, sedation, and weight gain, and >75% of antipsychotics-users reported side effects.

Lindstrøm et al.17 reports 2001 total of 94% of side effects for patients under maintenance treatment.

Danborg et al.18 conclude that: “The use of antipsychotics cannot be justified based on the evidence we currently have. Withdrawal effects in the placebo groups make existing placebo-controlled trials unreliable.”

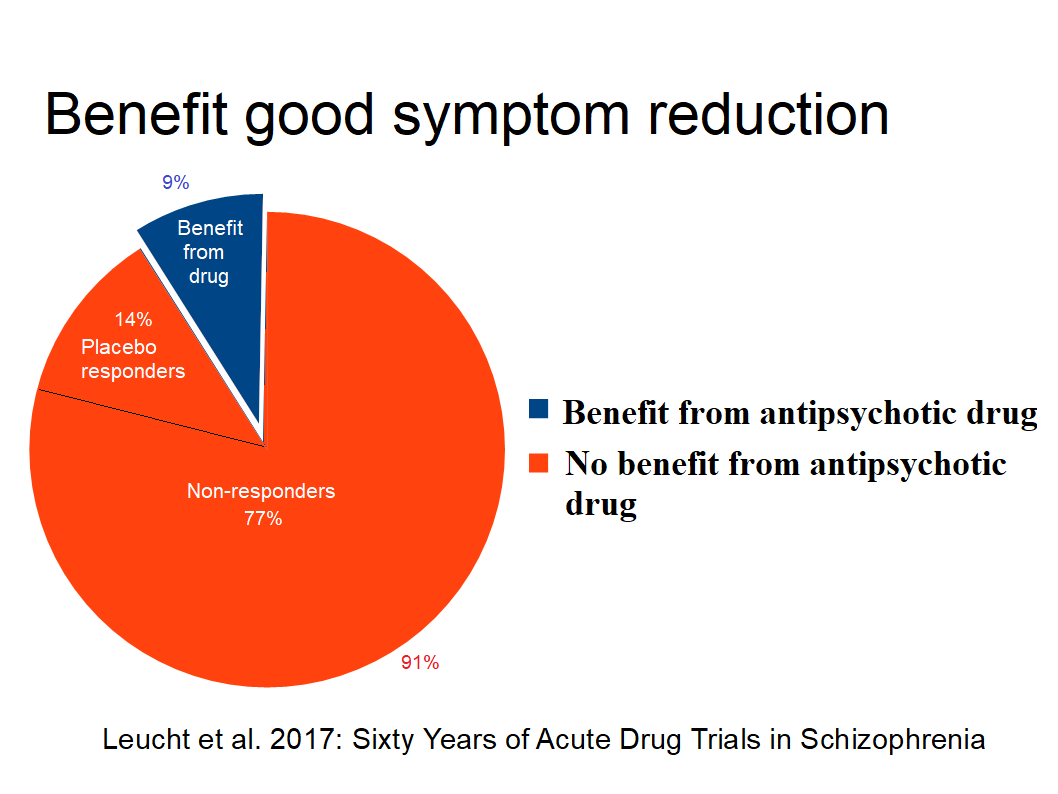

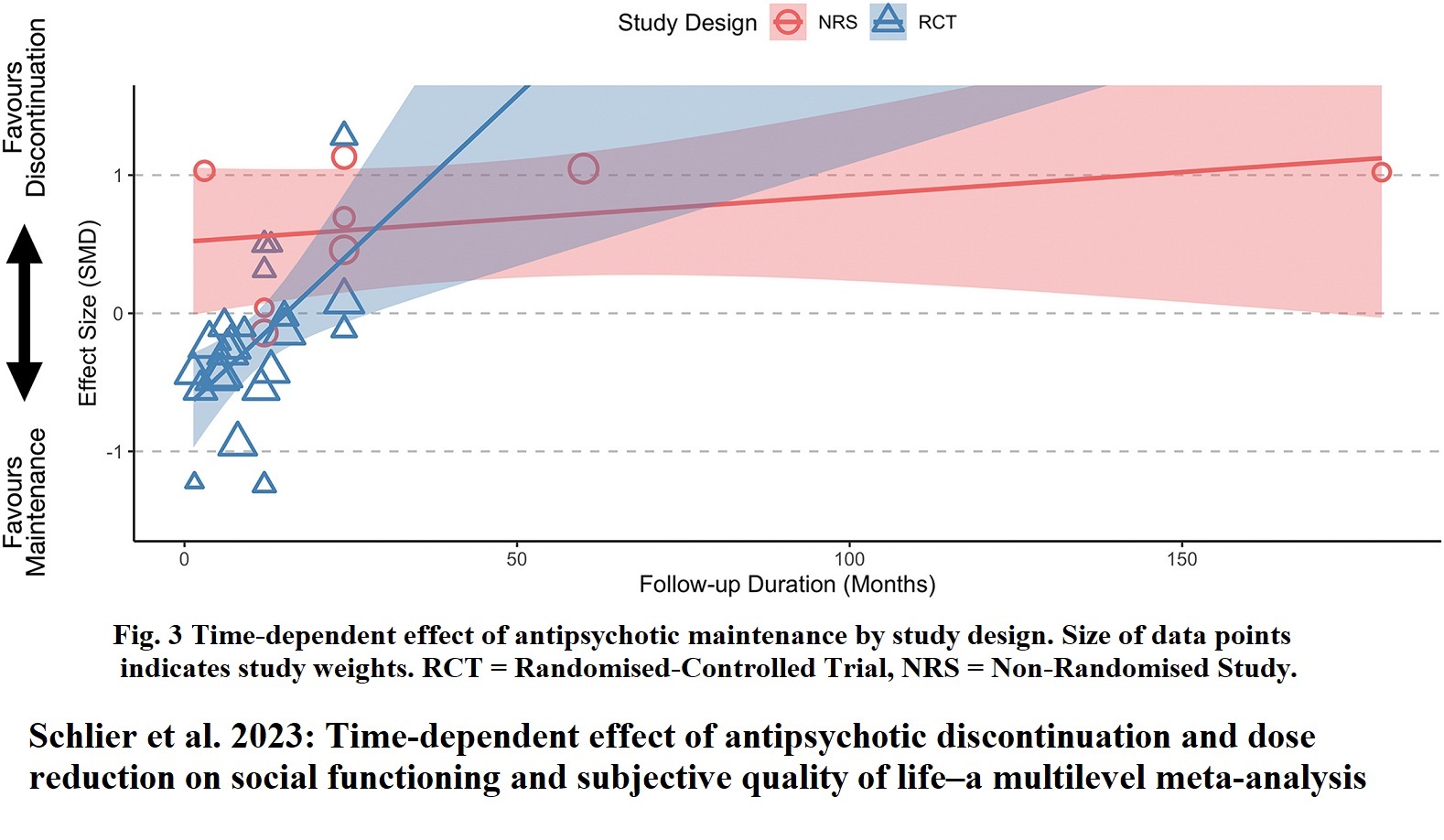

The strict claim of antipsychotic-naive research leaves the medication of nearly all patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia without justification and, therefore, maintenance results without relevance because of possible withdrawal effects. [Ceraso et al. 2020 found time-dependence. For more then 2 years to terminate medication is more preferable than maintenance (Schlier et al. 2023).]

According to Norwegian law, forced drugging can only be used when, with “high probability, it can lead to recovery or significant improvement in the patient’s condition, or if the patient avoids a significant worsening of the disease.” The Norwegian Ombudsman concluded in December 2018, with reference to the Psychiatry Act, that it violated the law to use forced treatment with an antipsychotic. Virtually all countries, apart from the United States, have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which prohibits forced drugging, but as far as I know not a single country has done anything.” (Peter C. Gøtzsche, 201919).

In 2011, Germany’s Constitutional Court declared the regulations on coercive treatment in two German states unlawful, which effectively stopped coercive antipsychotic treatment in these parts of Germany. In 2012, Germany’s Federal Supreme Court followed these rulings and extended the ban on coercive antipsychotic treatment across Germany when it found the regulations governing coercive treatment in German guardianship law unconstitutional (Zinkler 201620). Germany was without coercive treatment in psychiatry. This real-world experience proves that it is possible to ban forced treatment. Afterwards, criteria for coercive treatment were narrowed, and procedural safeguards were introduced. In Bavaria, the use of forced drugging was reduced from 2of-8% to 0.5% for inpatients.

Flammer et al.21 reported 2018 that in the German state of Baden-Württemberg 0.6 % of inpatients were affected by forced medication either as an emergency or after a judge's decision in 2016. Coercive medication is rarely used.

Inspired by this success, the head of doctors, Martin Zinkler22 at the Heidenheim Klinik in Germany, suggested “End Coercion in Mental Health Services—Toward a System Based on Support Only”.

There is obviously a gap between evidence and practice. The Tapering Anti-Psychotics and Evaluating Recovery (TAPER) Research Consortium is addressing this gap (Koops et al. 202323). There is no clear consensus about how long maintenance treatment should last, with a growing emphasis on the patient perspective, many alarming side effects, and patients discontinuing medication.

Based on previous and currently ongoing studies, the TAPER group aims to provide the field with evidence-based guidelines on low-dose medication and the reduction/discontinuation of antipsychotic medication. However, the obvious question of how many patients should be medicated at the start is not to be included.

Begemann et al. 202024 started “To continue or not to continue? Antipsychotic medication maintenance versus dose-reduction/discontinuation in first episode psychosis: HAMLETT, a pragmatic multicenter single-blind randomized controlled trial” “investigating the effects of continuation versus dose-reduction/discontinuation of antipsychotic medication after remission of a first episode of psychosis (FEP) on personal and social functioning, psychotic symptom severity, and health-related quality of life.” HAMLETT is the abbreviation for “Handling Antipsychotic Medication Long-term Evaluation of Targeted Treatment”. However, the question of how many patients should be medicated in the beginning is not included.

The DSM 1 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Mental Disorders) in 1952 considered both schizophrenic and psychotic sickness as reactions.

The DSM 3 defines schizophrenia by psychotic symptoms. The hope was to be able to identify disorders based on biological and genetic markers. But the biological understanding in the 70s and 90s was not confirmed by studies.

Francis Allen chair of DSM-IV criticized DSM V: “DSM-V opens up the possibility that millions and millions of people currently considered normal will be diagnosed as having a mental disorder and will receive medication and stigma that they don’t need.” (Kudlow et al. 201325)

After 40 years of using billions in research, no such genetic markers have been found. Steven Hyman26 former head of the NIMH from 1996 to 2001 found “a widely shared view that the underlying science remains immature and that therapeutic development in psychiatry is simply too difficult and too risky.” He describes using diagnostic classification systems as an 'epistemic prison'.

Director of NIMH from 2002 to 2015 Dr. Thomas Insel declared 201327 that “Patients deserve better… The weakness (of DSM) is its lack of validity... That is why NIMH will be re-orienting its research away from DSM categories.”

Trond F. Aarre28 found 2022 in “A Farewell to Psychiatric Diagnoses”: “The supervisory authorities believe that there is no justification for not using ICD-10 to make psychiatric diagnoses. However, research shows that the classification system is invalid...The link is weak between the diagnosis and the medication used. Few of those who use antipsychotics have ever been psychotic, and antidepressants are used for a great many mental health problems, with or without documentation of efficacy.”

The failure to find a biological basis promoted a new view of diagnosis and treatment. Jan Olav Johannessen et al. 202329 in “Modern Understanding of Psychosis: from Brain Disease to Stress Disorder”: "We must realize that today’s drugs for the most serious mental disorders are not as effective as one might hope". “The breakthrough in epigenetics, the understanding that gene expression is also influenced by the environment, by human experiences, has been crucial for modern understanding of causation in mental disorders. It seems that the significance of the genetic risk is much less than we previously assumed, perhaps as little as 5–6% of the risk.”

The recovery approach to mental health originally focused on helping people regain or stay in control of their lives. The meaning of recovery can be different for each person and may include (re)gaining meaning and purpose in life; being empowered and able to live a self-directed life; strengthening the sense of self and self-worth; having hope for the future; healing from trauma; and living a life with purpose. Mental health laws mention social and occupational recovery as being used to observe recovery results. Psychiatry has followed up with the term clinical recovery, focusing on symptom reduction. Recovery is a broad and multidimensional construct that has gained increasing attention and has now become mainstream for mental health legislation. Recovery outcomes are important to patients and society. WHO's Mental Health Action Plan 2013-202030 place emphasis on recovery. The WHO QualityRights31 initiative is improving quality and promoting human rights. Both the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the UK, and Ireland are building their national strategies for recovery.

Neuroleptics are used to ease symptoms and prevent relapse with uncertain evidence at the beginning of the psychosis in a minority of patients. There is no evidence that antipsychotics promote "psychosocial functioning, professional functioning, and quality of life" (Buchanan et al. 2009 PORT Treatment Recommendations32).

According to Leucht et al. 201233 nothing is known about the long-term effects of antipsychotic drugs compared to placebo. Future studies should focus on the,outcomes of social participation and clarify the long-term morbidity and mortality associated with these drugs.

Ceraso et al. have 202234 done a meta-analysis for preventing relapse after 1 year based on evidence from randomized trials. The trials are based on placebo group withdrawal effects that mimic or precipitate relapse, and therefore do therefore not meet strict scientific requirements. Reducing hospitalization was achieved NNT 9, remission of symptoms NNT 5, quality of life SMD = -0.32 and social functioning SMD = -0.43. Although the conversion to NNT is not straightforward, the SMD values convert approximately to NNT 10 for quality of life and NNT 7 for social functioning. There were no data on recovery.

Recovery rates decreased over 4 decades: «17.7% in studies between 1941 and 1955, 16.9% in 1956–1975, 9.9% in 1976–1995, and 6.0% in studies after 1996» according to Jaaskelainen et al. 201335.

Obviously, RTC studies do not provide evidence that antipsychotics promote recovery. Experience of historical development even suggests decreasing recovery over time.

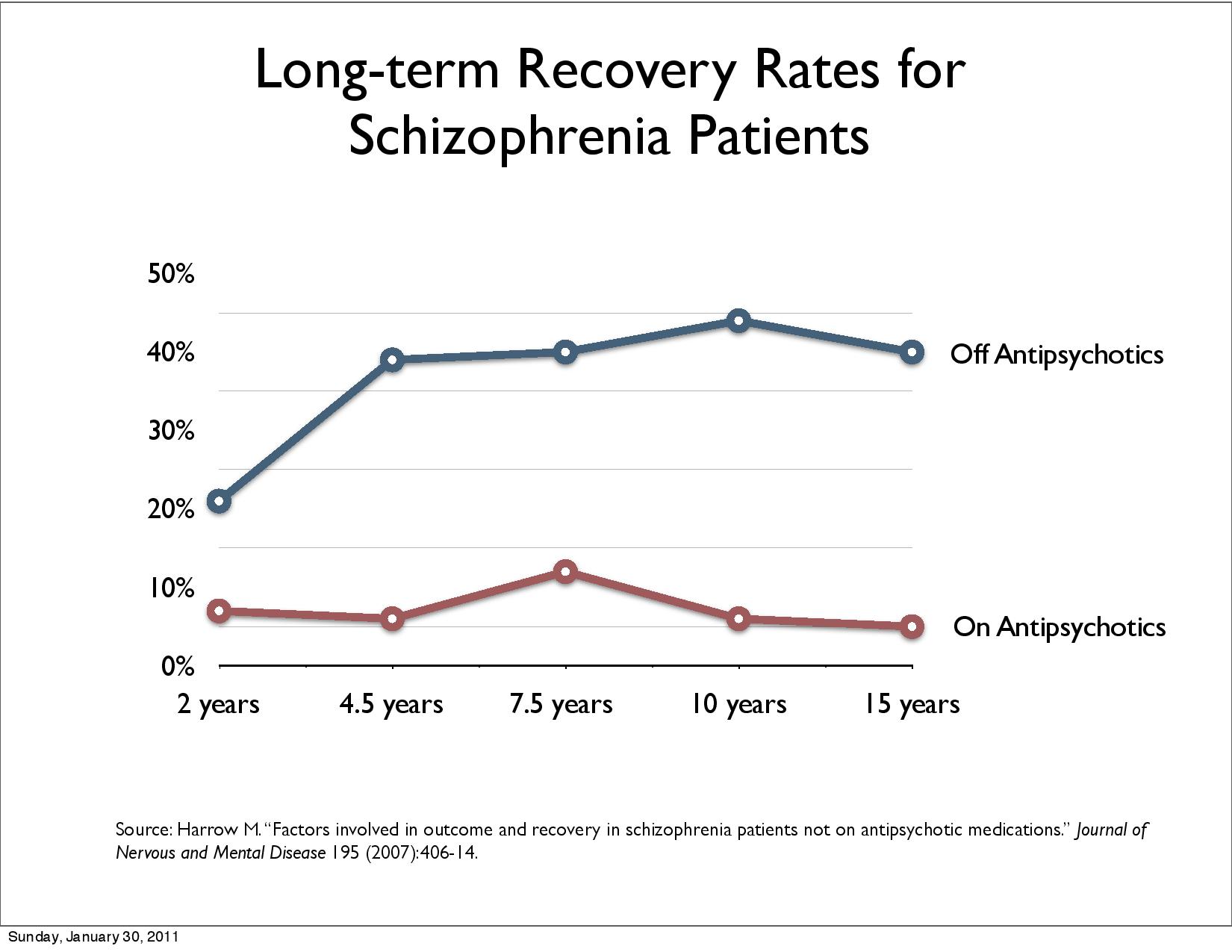

In the late 1970ties Harrow enrolled 200 psychotic patients in what became the best long-term, prospective study of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders ever conducted in the United States. Harrow and Jobe36 periodically assessed how well they were doing. Were they symptomatic? In recovery? Employed? At every follow-up—at 2 years, 4.5 years, 10 years, 15 years, and 20 years—they also assessed the patients’ use of antipsychotic medications.

Patients off medication experienced a 7-fold better recovery (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Long-term Recovery Rates for Schizophrenic Patients

Harrow's results were criticized because it was no RTC study. Patients “off medication” could be healthier at the start. However, Harrows could show that patients with milder psychosis also deteriorated.

However, in 2013, Lex Wunderink37 of the Netherlands conducted a randomized study of 128 first-episode patients that served as a partial response to that criticism. The patients had been stabilized on antipsychotics and were then randomized to “treatment as usual” or to a drug-tapering treatment designed to get patients down to a low dosage or off medication altogether, and then followed for seven years.

Drug reduction/discontinuation gave 40% recovery, and maintenance gave 18% recovery.

Harrow concluded 201738:

"Negative evidence on the long-term efficacy of antipsychotics has emerged from our own longitudinal studies and the longitudinal studies of Wunderink, of Moilanen, Jääskeläinena and colleagues using data from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort Study, by data from the Danish OPUS trials (Wils et al. 2017) the study of Lincoln and Jung in Germany, and the studies of Bland in Canada, "(Bland RC and Orn H. (1978): 14-year outcome in early schizophrenia).”

Harrow, M. & Jobe, T.H.39 added 2018:

“(T)he Suffolk County study of Kotov et al in the US, and the long-term data provided by the the AESOP-10 study in England, ..., the Alberta Hospital Follow-Up Study in Western Canada, and the international follow-up study by Harrison et al are research programs included samples studied from 7 to 20 years. Unlike short-term studies, none of them showed positive long-term results.”

Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), a randomized clinical trial that compared 5 representative antipsychotic medications, up to 18 months for 1124 participants. Trajectory analysis of the entire sample identified that 18.9% of participants belonged to a group of responders. This figure increased to 31.5% for completers, and fell to 14.5% for dropouts. 72% of participants are dropouts (Levine et al. 201240).

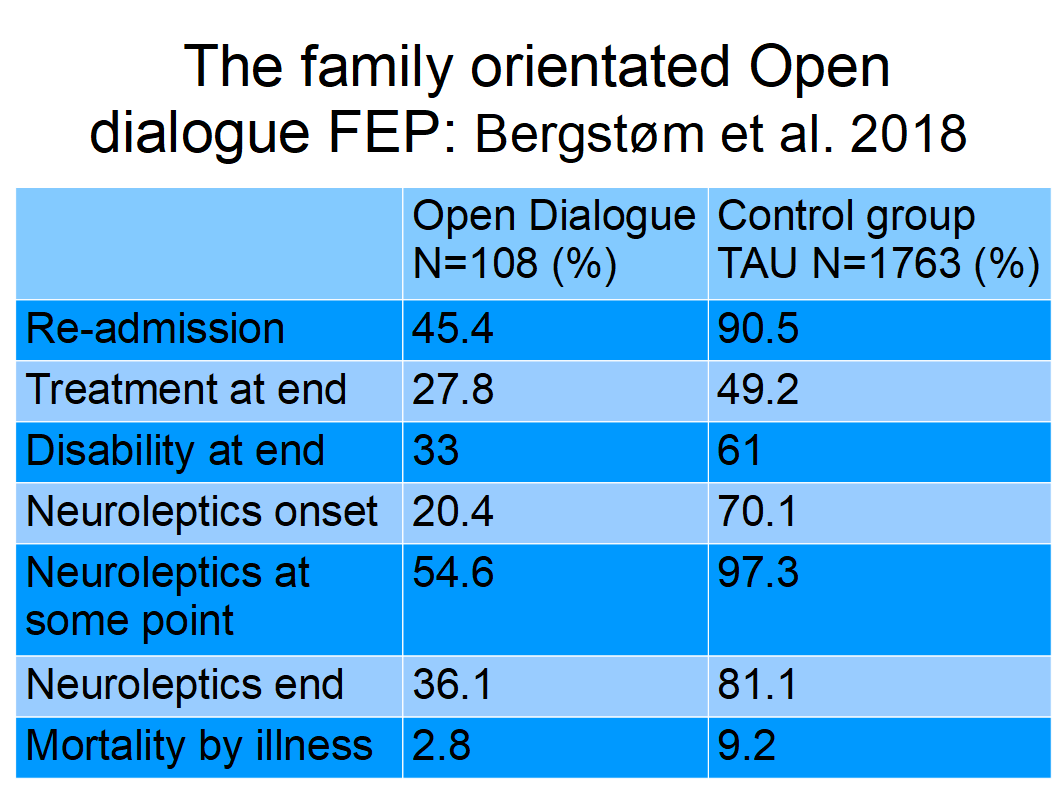

Bergström et al. 201841 compared Open dialogue patients in northern Finland with all FEP patients in Finland over a period of 19 years. Open dialogue (OD) uses neuroleptics for 20% of patients in the beginning, standard treatment (CG control group) 70%. 97,3 % of the CG get neuroleptics at some point. At the end, 36% of OD patients use neuroleptics, for CG it is 81%.Disability allowance, readmission and patients under treatment halves with OD. Randomisation should guarantee that patients are evenly distributed among groups. This study is based on a “natural randomisation” and the study discusses that the open dialogue area is comparable the rest of Finland with small discrepancies. Comparison with traditional RTC studies shows advantages of this study:

No selection bias because all patients in both groups are included

At onset only 20.4% of patients are medicated in the Open dialogue area i.e. 80% are antipsychotics naïve and avoids this weakness of traditional RCTs

Disability, readmission, and patients under treatment reflects recovery better than symptom reduction

long-term recovery is covered an area traditional RCTs do not cover

Figure 4: Nineteen–year outcomes: The family-oriented open dialogue approach in the treatment of first-episode psychosis

It is easy to observe that medicating nearly all patients diagnosed with schizophrenia can and should be disputed. However, defenders of TAU simply ignore this. Projects like “Antipsychotic Discontinuation and Reduction” (RADAR42), TAPER, and “Handling Antipsychotic Medication Long-term Evaluation of Targeted Treatment” (HAMLETT43) start by stating that “Antipsychotic medication is effective in diminishing severity of psychotic symptoms and in reducing the risk for psychotic relapse” and “most guidelines recommend continuation of treatment with antipsychotic medication for at least 1 year.” However, patients preferences to stop are caused by the negative side effects of antipsychotic medication, such as weight gain, anhedonia, sedation, sexual dysfunction, and parkinsonism. Therefore, evidence to guide patients and clinicians regarding questions concerning optimal treatment duration and when to taper off medication after remission of a FEP is needed.

However, the missing basis for medicating all is not even mentioned, i.e. 9% acute good symptom reduction due to antipsychotics with nearly no contribution to recovery. Obviously, much withdrawal can be avoided by not medicating all (Bergström et al. 2018). Missing validity of DSM/ICD diagnosing and its consequences on medicating is neglected.

TAPER, RDAR, and MAMLETT trials are done by approximately five dozen leading scientists in psychiatry.

Due to the low symptom reduction and lack of recovery effect, many patients want to stop taking antipsychotics. This is obviously urgent for non-responders, who have no advantage from antipsychotics, only the disadvantage of side effects. Psychiatric literature stipulates 20% to 30% non-responders. However, Leucht et al. found in 2017 that 79% did not respond with acute good symptom reduction, and 91% had no benefit of drugs. According to Samara et al. 201944 19.8% of patients experience an even symptom increase, approximately half clinically observable. 43% do not respond for cut-off 25% (minimal) and 66,5% for 50% cut-off (good) reduction. The overall percentage of no symptomatic remission was 66.9% .

From patients perspective the wish to stop treatment that does not help seems logical. But psychiatrists are not informed about the magnitude of the problem and underestimate non-responders. Non-conformance of patients is attributed to lack of insight due to illness, negative attitude towards treatment, substance use or abuse, and poor therapeutic alliance.

John Read et al. 202045 reported in “Using Open Questions to Understand 650 People's Experiences With Antipsychotic Drugs”

“Of the total participants, 14.3% were categorized as reporting purely positive experiences, 27.9% had mixed experiences, and 57.7% reported only negative ones. Negative experiences were positively correlated with age. Thematic analysis identified 749 negative, 180 positive, and 53 mixed statements ... The 4 negative themes (besides "unspecified"-191) were: "adverse effects" (316), "interactions with prescriber" (169), "withdrawal/difficult to get off them" (62), and "ineffective" (11).

Read and Williams46 conducted “Positive and Negative Effects of Antipsychotic Medication: An International Online Survey of 832 Recipients” with 832 participants with experiences with antipsychotics scientists found:

“Results: Over half (56%) thought the drugs reduced the problems they were prescribed for, but 27% thought they made them worse. Slightly less people found the drugs generally ‘helpful’ (41%) than found them ‘unhelpful’ (43%). While 35% reported that their ‘quality of life’ was ‘improved’, 54% reported that it was made ‘worse’. The average number of adverse effects reported was 11, with an average of five at the ‘severe’ level. Fourteen effects were reported by 57% or more participants, most commonly: ‘Drowsiness, feeling tired, sedation’ (92%), ‘Loss of motivation’ (86%), ‘Slowed thoughts’ (86%), and ‘Emotional numbing’ (85%). Suicidality was reported to be a side effect by 58%. Older people reported particularly poor outcomes and high levels of adverse effects. Duration of treatment was unrelated to positive outcomes but significantly related to negative outcomes. Most respondents (70%) had tried to stop taking the drugs. The most common reasons people wanted to stop were the side effects (64%) and worries about long-term physical health (52%). Most (70%) did not recall being told anything at all about side effects.”

Lindstrøm et al.47 examined “Patient-rated versus clinician-rated side effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. Clinical validation of a self-rating version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale”. All side effects summed up to 94% of patients. The study found a varying but statistically significant correlation between patient and clinician rated side effects. The highest correlations were found for items belonging to the sub-groups Psychic and Autonomic Side Effects, and the lowest in the subgroup of Neurological Side Effects. Patients reported the side effects more frequently and more severely than the clinicians.

Lacro et al 200248 reported non-adherence rates in schizophrenia range between 40% and 50%, Vega et al. 202149 reported non-adherence was high (58.2%) in the six-month post-discharge period.

Lieberman et al. 201150 stated «The most striking result of the CATIE study, which enrolled almost 1,500 individuals with chronic schizophrenia, was the high rate of treatment discontinuation (up to 74%) over the 18-month period of the trial and the short median time to discontinuation of treatment (about 6 months) in all phases of the trial.». The initial CATIE report 2005 has been cited in the literature over 1,600 times.

Koops et al. 202351: Addressed the evidence to practice gap: “What to Expect From International Antipsychotic Dose Reduction Studies in the Tapering Anti-Psychotics and Evaluating Recovery Consortium?”: «Within the first year of treatment, up to 58% of patients discontinue medication without consulting their professional caregivers».

Due to low effect and many side effects, many patients stop taking antipsychotics, seen as non-adherence by psychiatrists caused by a lack of insight. Many patients want medication-free treatment (Standal 202152) opposed by psychiatrists.

McHugh et al.53 concluded 2013: “Aggregation of patient preferences across diverse settings yielded a significant 3-fold preference for psychological treatment. Given evidence for enhanced outcomes among those receiving their preferred psychiatric treatment and the trends for decreasing utilization of psychotherapy, strategies to maximize the linkage of patients to preferred care are needed.”

As mentioned above, Zinkler et al. suggested in 2019 “End Coercion in Mental Health Services—Toward a System Based on Support Only”. However, the reactions are disappointing.

The suggestion elicited a lot of responses, among them rather strong and emotionally laden reactions by mainstream psychiatry (von Peter et al. 202154). Zinkler and von Peter wrote about how to cope with criticism and embrace change and came up with further reflections on the debate on a mental health care system without coercion using three strategies:

“The first strategy regards capacity building as a means to change the attitudes and practices of the stakeholders to better promote human rights of the user of psychiatry.

The second strategy targets the transformation of the mental health care system and related services.

The third strategy recommends aligning policy and law with the principles of the Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities (CRPD).”

The study “Conflict and Antagonism in Global Psychiatry” by Oute55 published in Sociology of Health and Illness, systematically examines more formal responses to the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur:

“Between 2017 and 2020, the UN Special Rapporteur (SR) Dainius Puras published three reports that called for significant changes to organisation, funding and service provision in mental health care in ways that emphasise inclusive, rights-oriented, democratic and sustainable community health services. This article aims to examine formal organisational responses to the UN mental health reports and consider the underlying arguments that either support or delegitimise the SR stance on the need for a paradigmatic shift towards a human rights-based approach to mental health. By combining several different search strategies to identify organisational responses across the web, a total of 13 organisational responses were included in the analysis.”

13 responses were analysed, most of which were hostile criticisms of the reports, written in open letter form by medical or psychiatric organisations such as the World Medical Association, the European Brain Council, the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology and so on.

The headlines of the findings are:

“Binary positions and contesting articulations of good mental health care

Psychiatric stakeholders have authority

The SR is unscientific and dangerous

Abandoning biomedicine and long-term psychiatric care would be harmful

Psychiatry is scientific and ethical

Psychiatry is a branch of medicine

Psychiatric science always advances

Critiques of the biomedical paradigm are wrong

Psychiatric pluralism is a common sense

Rejecting the SR reports in defence of psychiatry

The report damages patient trust in psychiatrists

The report is offensive and unfair

Failures in mental health care are located in society, governments, and patients”

The following conclusions are drawn:

“Binary positions and contesting articulations of good mental health care and ‘Rejecting the UN reports in defence of Psychiatry’. Within these were subthemes that are presented as ‘givens’, facts or truths, which are upheld within the discourse employed by the respective organisations. The majority of stakeholder responses from medical and psychiatric organisations rejected and heavily criticised the SR position. In contrast, the British Psychological Society and Mental Health Europe (behalf of over 50 organisations) response firmly endorsed and aligned with the SR’s reports... The represented binary, for example, echoes the ‘martyr and the enemy’ rhetoric and ‘ex-communication’ strategies, given the SR is rhetorically positioned as a rogue anti-psychiatrist, violating professional norms and victimising psychiatry at large.”

The discussion documents a broken dialogue and seems to show a discussion deadlock.,

However, in 2020, the World Psychiatric Association took a more constructive position and published a position statement56“Implementing Alternatives to Coercion: A Key Component of Improving Mental Health Care” which is broadly in line with the UN recommendations e. g. CRPD. The statement recognizes “the substantive role of psychiatry in implementing alternatives to coercion in mental health care” and “the WPA wishes to emphasise that implementing alternatives to coercion is an essential element of the broader transition across the mental health sector toward recovery-oriented systems of care.”

The CRPD Committee stated in General Comment no. 1, 2014, CRPD/C/GC/157, paragraph 42 clearly to stop forced treatment:

“As has been stated by the Committee in several concluding observations, forced

treatment by psychiatric and other health and medical professionals is a violation of the

right to equal recognition before the law and an infringement of the rights to personal

integrity (art. 17); freedom from torture (art. 15); and freedom from violence, exploitation

and abuse (art.

16).

State parties must abolish policies and legislative

provisions that allow or perpetrate forced treatment, as it is an

ongoing violation found in mental health laws across the globe,

despite empirical evidence indicating its lack of effectiveness and

the views of people using mental health systems who have experienced

deep pain and trauma as a result of forced treatment.”

Treatment as usual (TAU) is based on antipsychotics as a cornerstone, which are considered well documented and undisputed. Nearly all patients diagnosed schizophrenia are medicated with antipsychotics. However, long-term evidence treatment is well known since the 50ties. Strict scientific standards disclose that antipsychotic naive patients are missing in studies making acute and first-episode psychosis treatment efficiency uncertain.

Claims about the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication are often of qualitative character and not quantified and substantiated by research. Studies are referred e.g., “antipsychotics proved to be more effective than placebo”:

lack information of the type of effect (symptom reduction),

no awareness of lack of antipsychotic naive participants

placebo bigger than effect due to medication

The narrative that it would be unethical not to medicate was based on the background that randomization to placebo was done after a wash-out period with all participants on drugs. This narrative is no longer valid according to Bola: “Antipsychotic medication for early episode schizophrenia”58. Low unsure symptom-reduction can not justify medicating nearly all patients diagnosed schizophrenia, especially non-responders. The aim of treatment according to mental health laws is recovery which is not achieved by antipsychotics.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health59 notes that diagnostic tools, such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the DSM, continue to expand the parameters of individual diagnosis, often without a solid scientific basis. Moreover, we have been sold the myth that the best solutions for addressing mental health challenges are medications and other biomedical interventions. The urgent need for a shift in approach should target social determinants and abandon the predominant medical model that seeks to cure individuals by targeting disorders. Mental health policies should address the “power imbalance” rather than the “chemical imbalance”.

That is why the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health Mr. Puras has called for «World needs "revolution" in mental health care» due to "unequivocal evidence of the failures of a system that relies too heavily on the biomedical model of mental health services, including the front-line and excessive use of psychotropic medicines, and yet these models persist".

WHO60 followed up with the “(n)ew WHO guidance (which) seeks to put an end to human rights violations in mental health care”: "This comprehensive new guidance provides a strong argument for a much faster transition from mental health services that use coercion and focus almost exclusively on the use of medication to manage symptoms of mental health conditions, to a more holistic approach that takes into account the specific circumstances and wishes of the individual and offers a variety of approaches for treatment and support". Compulsory Community Treatment Orders and forced injections of antipsychotics are ineffective and unethical.

“We found that people with mental illness frequently state that recovery is a journey, characterized by a growing sense of agency and autonomy, as well as greater participation in normative activities, such as employment, education, and community life. However, the evidence suggests that most people with SMI still live in a manner inconsistent with recovery; for example, their unemployment rate is over 80%, and they are disproportionately vulnerable to homelessness, stigma, and victimization. Research stemming from rehabilitation science suggests that recovery can be enhanced by various evidence-based services, such as supported employment, as well as by clinical approaches, such as shared decision making and peer support. But these are not routinely available. As such, significant systemic changes are necessary to truly create a recovery-oriented mental health system.”

The implementation of QualityRights for attitudinal change towards the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) human rights among participants through the delivery of the QualityRights training has been evaluated (Morrissey 202061).

“Attitudinal changes towards CRPD rights were found in all except one of the evaluation statements from pre- to post-training. Three-quarters of the statements showed attitudinal changes between 10 and 40 percent. The highest levels of attitudinal change were in relation coercion (i.e. involuntary detention; treatment and seclusion); independent living; legal capacity; and resources. Sixty percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the training changed their attitude towards persons with psychosocial, intellectual and cognitive disabilities. Similar attitudinal changes towards CRPD rights were found among service provider participants.”

The CRPD is an international human rights treaty of the United Nations intended to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities e.g. psychosocial disabilities. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that persons with disabilities enjoy full equality under the law.

The WHO-OHCHR guidance launched October 2023 seeks to improve laws addressing human rights abuses in mental health care (WHO-OHCHR 202362) to support countries in reforming legislation in order to end human rights abuses and increase access to quality mental health care.

“While many countries have sought to reform their laws, policies and services since the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006, too few have adopted or amended the relevant laws and policies on the scale needed to end abuses and promote human rights in mental health care.”

One of the reasons is to improve treatment. A fundamental shift is required within the field of mental health. Stigma, discrimination, and other human rights violations continue in mental health care settings. The report identifies the "biomedical model of mental health" as the root of many problems. There is an overreliance on biomedical approaches to treatment options, inpatient services, and care, and little attention given to social determinants and community-based, person-centered interventions. Legislation can help ensure that human rights underpin all actions in the field of mental health.

Treatment-As-Usual (TAU) did not improve patients recovery, mainly due to resistance to giving up excessive medication. Legislators can solve this deadlock by following OHCHR suggestions and removing legal permission for forced drugging. This could promote a shift of paradigm of treatment of schizophrenia towards recovery.

Conflicts of Interest Statement: The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

No funding was received for conducting this study.

List of figures:

Figure 1: Rappaport Study: Three-Year Outcome

Figure 2: Good acute symptom reduction

Figure 3: Long-term Recovery Rates for Schizophrenic Patients

Figure 4: Nineteen–year outcomes: The family-oriented open dialogue approach in the treatment of first-episode psychosis

References:

1O ODEGARD. PATTERN OF DISCHARGE FROM NORWEGIAN PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITALS BEFORE AND AFTER THE INTRODUCTION OF THE PSYCHOTROPIC DRUGS. Am J Psychiatry. 1964 Feb:120:772-8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.120.8.772.

2Bockoven, J. S., & Solomon, H. C. (1975). Comparison of two five-year follow-up studies: 1947 to 1952 and 1967 to 1972. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 132(8), 796–801. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.132.8.796

3Cole, J. The National Institute of Mental Health Psychopharmacology Service Center. Collaborative Study Group. Phenothiazine treatment in acute schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 10 (1964): 246–61.

4N R Schooler, S C Goldberg, H Boothe, J O Cole. One year after discharge: community adjustment of schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1967 Feb;123(8):986-95. doi: 10.1176/ajp.123.8.986.

5M Rappaport, H K Hopkins, K Hall, T Belleza, J Silverman. Are there schizophrenics for whom drugs may be unnecessary or contraindicated? Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1978;13(2):100-11. doi: 10.1159/000468327.

6Whitaker R: The Case Against Antipsychotics: A Review of Their Long-Term Side Effects. Cambridge, Mass, Mad in America Foundation, 2016 https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/07/the-case-against-antipsychotics/

7Whitaker R: The Case Against Antipsychotics: A Review of Their Long-Term Side Effects. Cambridge, Mass, Mad in America Foundation, 2016 https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/07/the-case-against-antipsychotics/

8Leucht, S., Arbter, D., Engel, R. et al. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry 14, 429–447 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002136

9Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;(5):CD008016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008016.pub2

10Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, Chaimani A, Mavridis D, Helfer B, Samara M, Rabaioli M, Bächer S, Cipriani A, Geddes JR, Salanti G, Davis JM. Sixty Years of Placebo-Controlled Antipsychotic Drug Trials in Acute Schizophrenia: Systematic Review, Bayesian Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of Efficacy Predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 1;174(10):927-942. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121358. Epub 2017 May 25. PMID: 28541090.

11Robert Whitaker. The case against antipsychotic drugs: a 50-year record of doing more harm than good. Medical Hypotheses Volume 62, Issue 1, January 2004, Pages 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00293-7

12Whitaker R: The Case Against Antipsychotics: A Review of Their Long-Term Side Effects. Cambridge, Mass, Mad in America Foundation, 2016 https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/07/the-case-against-antipsychotics/

13Sohler N, Adams BG, Barnes DM, Cohen GH, Prins SJ, Schwartz S. Weighing the evidence for harm from long-term treatment with antipsychotic medications: A systematic review. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(5):477-485. doi:10.1037/ort0000106

14Robert Whitaker. The Case Against Antipsychotics. online publication July 25, 2016. https://www.madinamerica.com/2016/07/the-case-against-antipsychotics/

15Dalsbø TK, Dahm, KT, Øvernes, LA, Lauritzen M, Skjelbakken T. [Effectiveness of treatment for psychosis: evidence base for a shared decision-making tool] Rapport 2019. Oslo: Folkehelseinstituttet, [Norwegian Institute of Public Health ] 2019.

16Iversen TSJ, Steen NE, Dieset I, et al. Side effect burden of antipsychotic drugs in real life - Impact of gender and polypharmacy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;82:263-271. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.11.004 Nov 7. PMID: 29122637.

17Lindström E, Lewander T, Malm U, Malt UF, Lublin H, Ahlfors UG. Patient-rated versus clinician-rated side effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. Clinical validation of a self-rating version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU-SERS-Pat). Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55 Suppl 44:5-69. doi:10.1080/080394801317084428

18Danborg PB, Gøtzsche PC. Benefits and harms of antipsychotic drugs in drug-naïve patients with psychosis: A systematic review. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2019;30(4):193-201. doi:10.3233/JRS-195063

19Gøtzsche PC. Forced Drugging with Antipsychotics is Against the Law: Decision in Norway online publication Cambridge, Mass, Mad in America Foundation, 2016. https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/05/forced-drugging-antipsychotics-against-law/

20Zinkler, M. Germany without Coercive Treatment in Psychiatry—A 15 Month Real World Experience. March 2016 Laws 5(1):15. DOI: 10.3390/laws5010015

21Flammer E, Steinert T. [The Case Register for Coercive Measures According to the Law on Assistance for Persons with Mental Diseases of Baden-Wuerttemberg: Conception and First Evaluation]. Psychiatr Prax. 2019;46(2):82-89. doi:10.1055/a-0665-6728

22Zinkler, Martin, and Sebastian von Peter. 2019a. End Coercion in Mental Health Services—Toward a System Based on Support Only. Laws 8: 19.

23Sanne Koops, Kelly Allott, Lieuwe de Haan, Eric Chen, Christy Hui, Eoin Killackey, Maria Long, Joanna Moncrieff, Iris Sommer, Anne Emilie Stürup, Lex Wunderink, Marieke Begemann, TAPER international research consortium, Addressing the Evidence to Practice Gap: What to Expect From International Antipsychotic Dose Reduction Studies in the Tapering Anti-Psychotics and Evaluating Recovery Consortium, Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2023;, sbad112, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbad112

24Begemann MJH, Thompson IA, Veling W, et al. To continue or not to continue? Antipsychotic medication maintenance versus dose-reduction/discontinuation in first episode psychosis: HAMLETT, a pragmatic multicenter single-blind randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):147. Published 2020 Feb 7. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3822-5

25Kudlow P. The perils of diagnostic inflation. CMAJ. 2013;185(1):E25-E26. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4371

26Hyman SE. The Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: The Problem of Reification. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Vol. 6:155-179 (Volume publication date 27 April 2010). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091532

27Insel, T. Post by Former NIMH Director Thomas Insel: Transforming Diagnosis. NMIH website 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20210509074446/https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis

28Aarre TF. A farewell to psychiatric diagnoses. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2022. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.22.0386

29Johannessen JO, Joa I. Modern understanding of psychosis: from brain disease to stress disorder. And some other important aspects of psychosis. Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches Volume 13, 2021 - Issue 4 doi: 10.1080/17522439.2021.1985162

30WHO. Mental health action plan 2013 – 2020 online publication 6 January 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021

31Funk M, Bold ND. WHO's QualityRights Initiative: Transforming Services and Promoting Rights in Mental Health. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22(1):69-75.

32Robert W. Buchanan, Julie Kreyenbuhl, Deanna L. Kelly, Jason M. Noel, Douglas L. Boggs, Bernard A. Fischer, Seth Himelhoch, Beverly Fang, Eunice Peterson, Patrick R. Aquino, William Keller, The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT Psychopharmacological Treatment Recommendations and Summary Statements, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 36, Issue 1, January 2010, Pages 71–93, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbp116

33Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W, Davis JM. Maintenance treatment with antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;(5):CD008016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008016.pub2

34Anna Ceraso, Jessie Jingxia Lin, Johannes Schneider-Thoma, Spyridon Siafis, Stephan Heres, Werner Kissling, John M Davis, Stefan Leucht, Maintenance Treatment With Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia: A Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 48, Issue 4, July 2022, Pages 738–740, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbac041

35Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296-1306. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbs130

36Harrow M, Jobe TH. Factors involved in outcome and recovery in schizophrenia patients not on antipsychotic medications: a 15-year multifollow-up study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(5):406-414. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000253783.32338.6e

37Wunderink L, Nieboer RM, Wiersma D, Sytema S, Nienhuis FJ. Recovery in Remitted First-Episode Psychosis at 7 Years of Follow-up of an Early Dose Reduction/Discontinuation or Maintenance Treatment Strategy: Long-term Follow-up of a 2-Year Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):913–920. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.19

38Martin Harrow, Thomas H. Jobe, Robert N. Faull, Jie Yang. A 20-Year multi-followup longitudinal study assessing whether antipsychotic medications contribute to work functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, Volume 256, 2017, Pages 267-274. ISSN 0165-1781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.069

39Harrow M, Jobe TH. Long-term antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia: does it help or hurt over a 20-year period? World Psychiatry Volume17, Issue2, June 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20518

40Stephen Z. Levine, Jonathan Rabinowitz, Douglas Faries, Anthony H. Lawson, Haya Ascher-Svanum. Treatment response trajectories and antipsychotic medications: Examination of up to 18months of treatment in the CATIE chronic schizophrenia trial. Schizophrenia Research, Volume 137, Issues 1–3, 2012, Pages 141-146, ISSN 0920-9964, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.014

41Tomi Bergström, Jaakko Seikkula, Birgitta Alakare, Pirjo Mäki, Päivi Köngäs-Saviaro, Jyri J. Taskila, Asko Tolvanen, Jukka Aaltonen. The family-oriented open dialogue approach in the treatment of first-episode psychosis: Nineteen–year outcomes. Psychiatry Research, Volume 270, 2018, Pages 168-175, ISSN 0165-1781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.039

42University College London. Research into Antipsychotic Discontinuation and Reduction. This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0514-20004)

43Begemann MJH, Thompson IA, Veling W, et al. To continue or not to continue? Antipsychotic medication maintenance versus dose-reduction/discontinuation in first episode psychosis: HAMLETT, a pragmatic multicenter single-blind randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):147. Published 2020 Feb 7. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3822-5

44Myrto T Samara, Adriani Nikolakopoulou, Georgia Salanti, and Stefan Leucht. How Many Patients With Schizophrenia Do Not Respond to Antipsychotic Drugs in the Short Term? An Analysis Based on Individual Patient Data From Randomized Controlled Trials. Schizophr Bull. 2019 Apr; 45(3): 639–646. Published online 2018 Jul 2. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby095

45John Read, Ann Sacia. Using Open Questions to Understand 650 People's Experiences With Antipsychotic Drugs. Schizophr Bull. 2020 Jul 8;46(4):896-904. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa002

46Read J, Williams J. Positive and Negative Effects of Antipsychotic Medication: An International Online Survey of 832 Recipients. Curr Drug Saf. 2019;14(3):173-181. doi:10.2174/1574886314666190301152734

47Lindström E, Lewander T, Malm U, Malt UF, Lublin H, Ahlfors UG. Patient-rated versus clinician-rated side effects of drug treatment in schizophrenia. Clinical validation of a self-rating version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU-SERS-Pat). Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55 Suppl 44:5-69. doi:10.1080/080394801317084428

48Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(10):892-909. doi:10.4088/jcp.v63n1007

49Dulcinea Vega, Francisco J. Acosta, Pedro Saavedra. Non-adherence after hospital discharge in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: A six-month naturalistic follow-up study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, Volume 108, 2021, 152240, ISSN 0010-440X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2021.152240

50Jeffrey A. Lieberman, M.D., and T. Scott Stroup. The NIMH-CATIE Schizophrenia Study: What Did We Learn? The American Journal of Psychiatry. Published Online:1 Aug 2011. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010039

51Sanne Koops, Kelly Allott, Lieuwe de Haan, Eric Chen, Christy Hui, Eoin Killackey, Maria Long, Joanna Moncrieff, Iris Sommer, Anne Emilie Stürup, Lex Wunderink, Marieke Begemann, TAPER international research consortium, Addressing the Evidence to Practice Gap: What to Expect From International Antipsychotic Dose Reduction Studies in the Tapering Anti-Psychotics and Evaluating Recovery Consortium, Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2023;, sbad112, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbad112

52Standal K, Solbakken OA, Rugkåsa J, Martinsen AR, Halvorsen MS, Abbass A, Heiervang KS. Why Service Users Choose Medication-Free Psychiatric Treatment: A Mixed-Method Study of User Accounts. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:1647-1660. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S308151

53McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, Otto MW. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595-602. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r07757

54Sebastian von Peter, Martin Zinkler. Coping with Criticism and Embracing Change—Further Reflexions on the Debate on a Mental Health Care System without Coercion. Laws 2021, 10(2), 22; https://doi.org/10.3390/laws10020022

55Jeppe Oute, Susan McPherson. Conflict and antagonism within global psychiatry: A discourse analysis of organisational responses to the UN reports on rights-based approaches in mental health. Sociology of Health & Illness, First published: 05 October 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13717

56World Psychiatric Association. Supporting and implementing alternatives to coercion in mental health care. https://www.wpanet.org/alternatives-to-coercion

57Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Eleventh session. 31 March–11 April 2014.General comment No. 1 (2014). https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD/C/GC/1&Lang=en

58Bola J, Kao D, Soydan H. Antipsychotic medication for early episode schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(6):CD006374. Published 2011 Jun 15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006374.pub2

59The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Dainius Puras “World needs “revolution” in mental health care – UN rights expert” online publication 06 June 2017. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2017/06/world-needs-revolution-mental-health-care-un-rights-expert?LangID=E

60WHO “New WHO guidance seeks to put an end to human rights violations in mental health care” online publication 10 June 2021. https://www.who.int/news/item/10-06-2021-new-who-guidance-seeks-to-put-an-end-to-human-rights-violations-in-mental-health-care

61F.E. Morrissey. An evaluation of attitudinal change towards CRPD rights following delivery of the WHO QualityRights training programme. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, Volume 13, 2020, 100410, ISSN 2352-5525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2019.100410

62WHO-OHCHR launch new guidance to improve laws addressing human rights abuses in mental health care. 9 October 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/09-10-2023-who-ohchr-launch-new-guidance-to-improve-laws-addressing-human-rights-abuses-in-mental-health-care